In June 2 American astronauts left Earth anticipating to invest 8 days on the International Space Station (ISS).

But after worries that their Boeing Starliner spacecraft was hazardous to fly back on, Nasa postponed Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore’s return up until 2025.

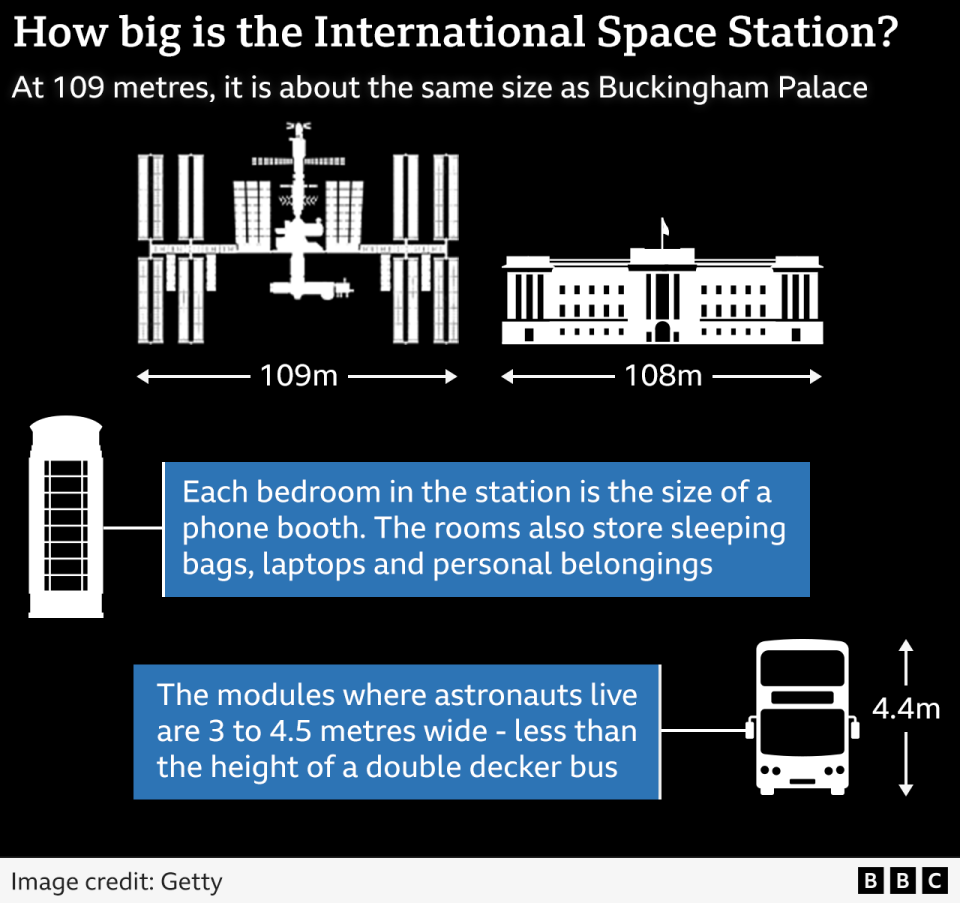

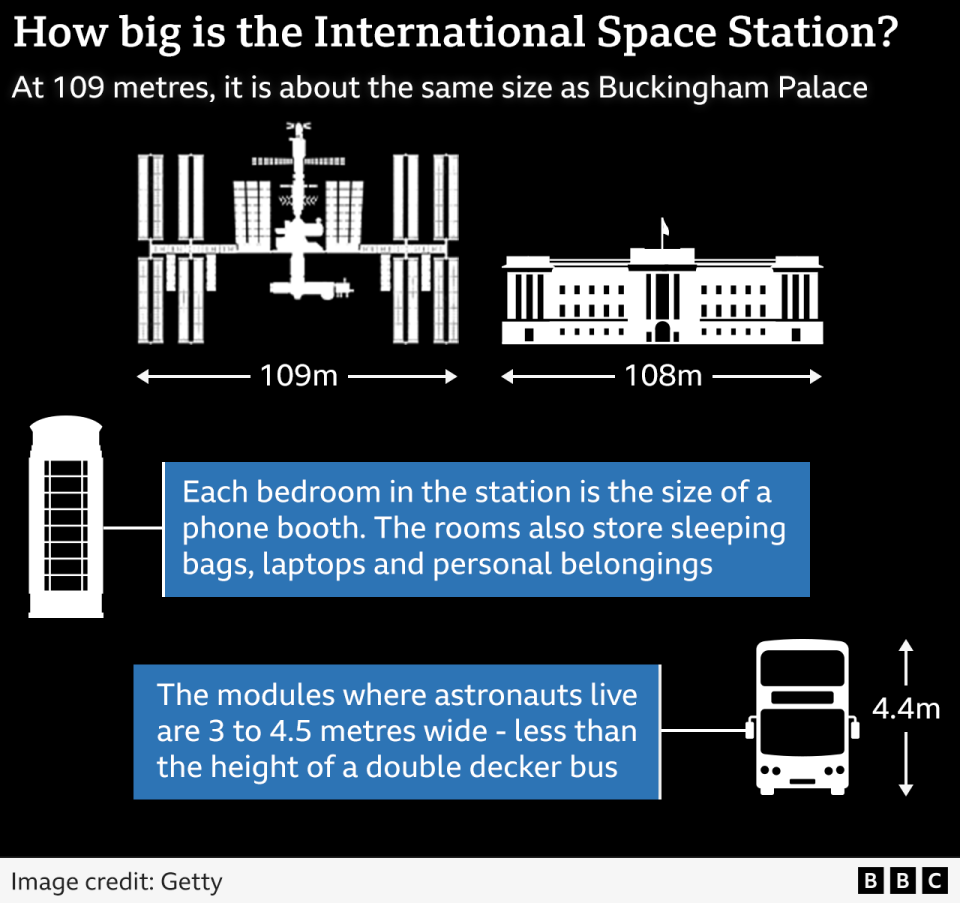

They are currently sharing an area regarding the dimension of a six-bedroom home with 9 other individuals.

Ms Williams calls it her “happy place” and Mr Wilmore claims he is “grateful” to be there.

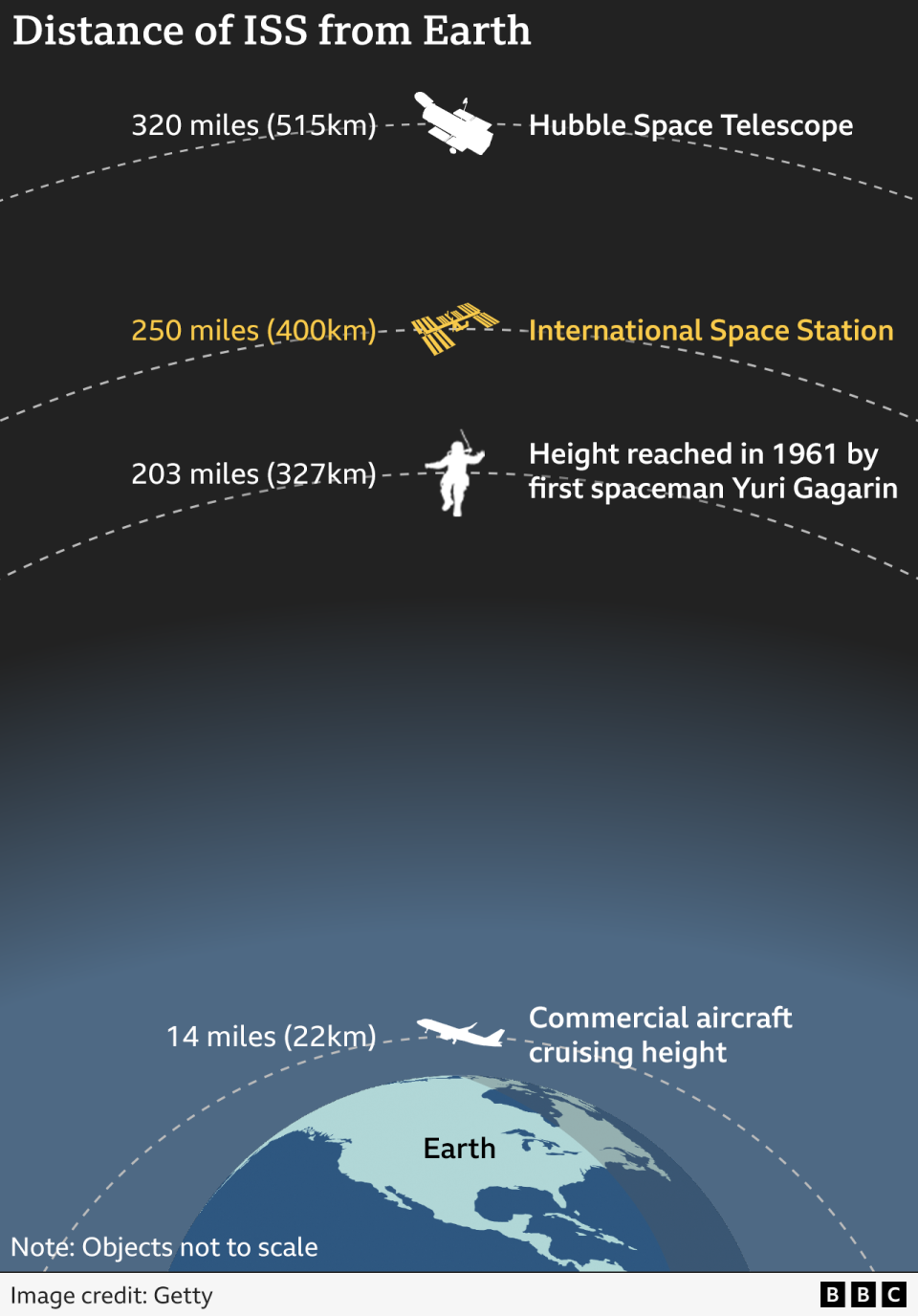

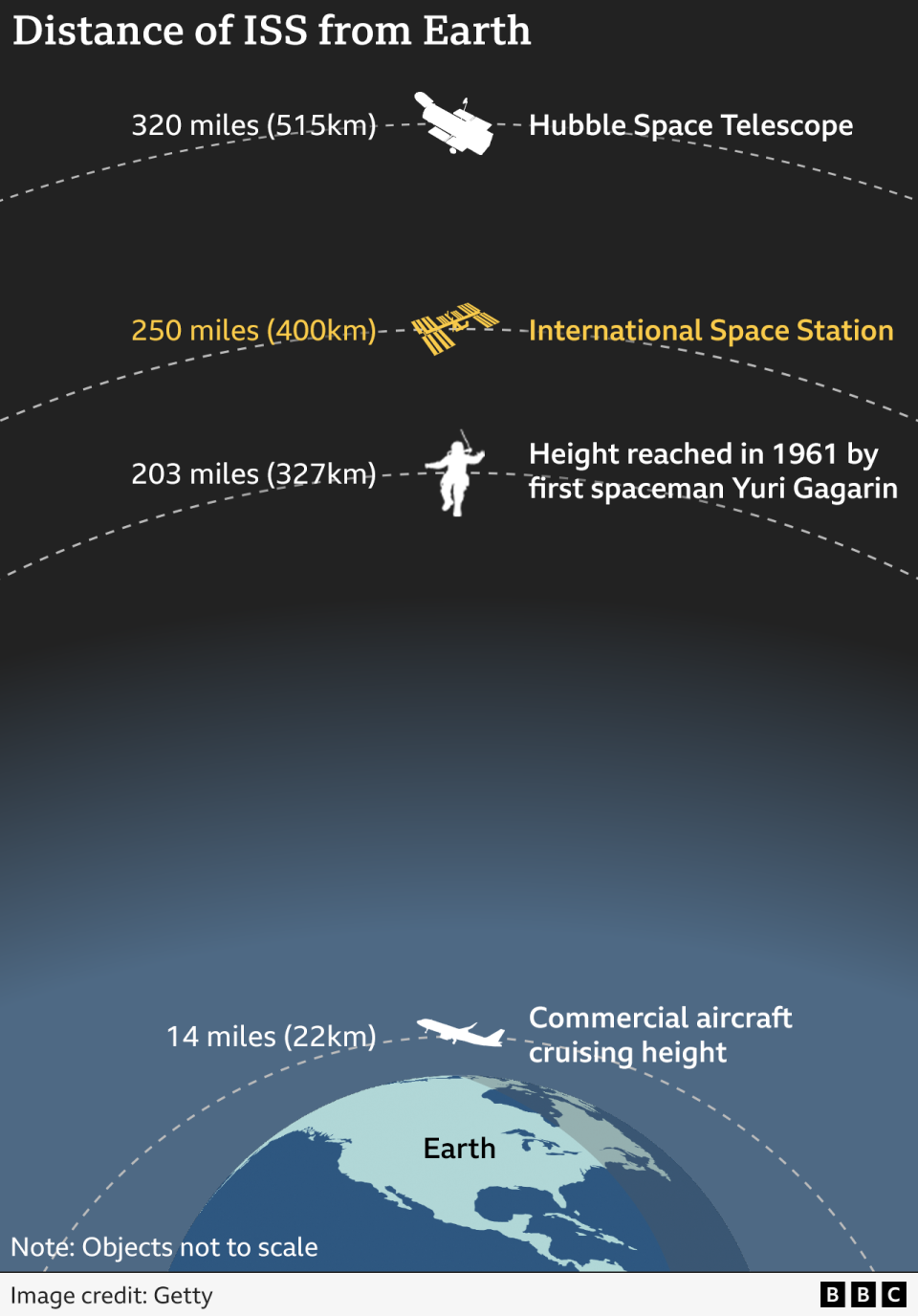

But exactly how does it actually feel to be 400km over Earth? How do you manage difficult crewmates? How do you work out and clean your clothing? What do you consume – and, significantly, what is the “space smell”?

Talking to BBC News, 3 previous astronauts reveal the tricks to enduring in orbit.

Every 5 mins of the astronauts’ day is separated up by goal control on Earth.

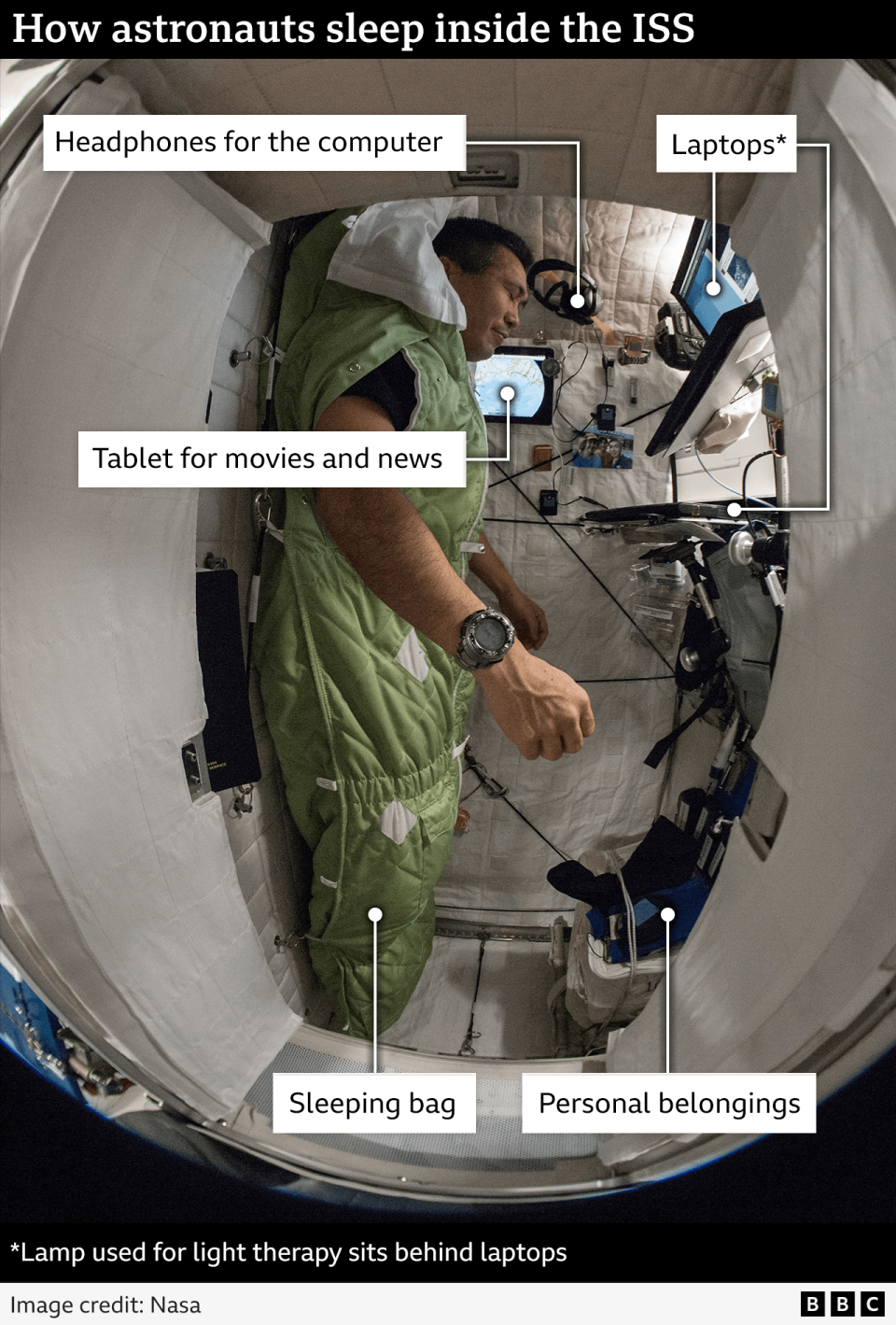

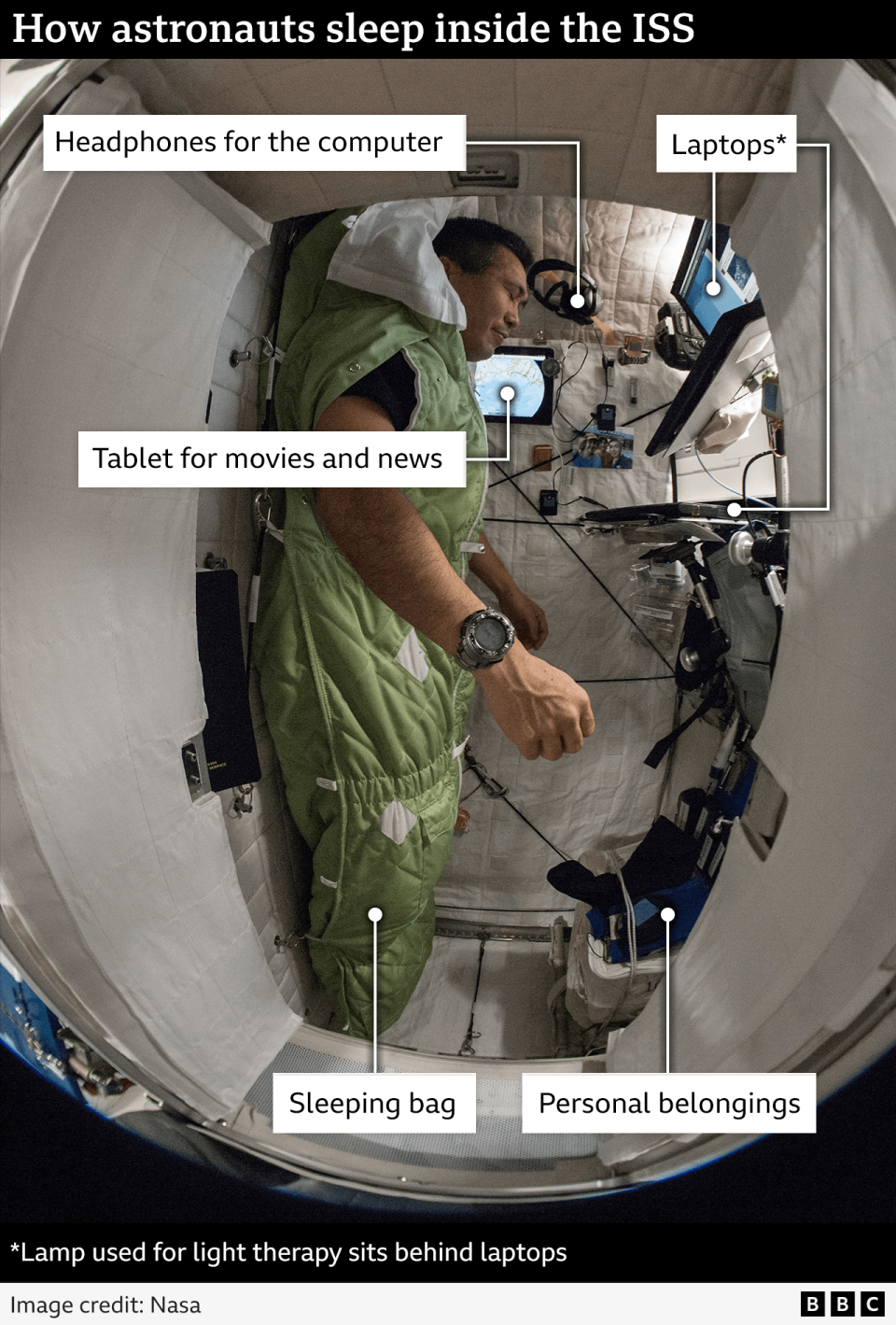

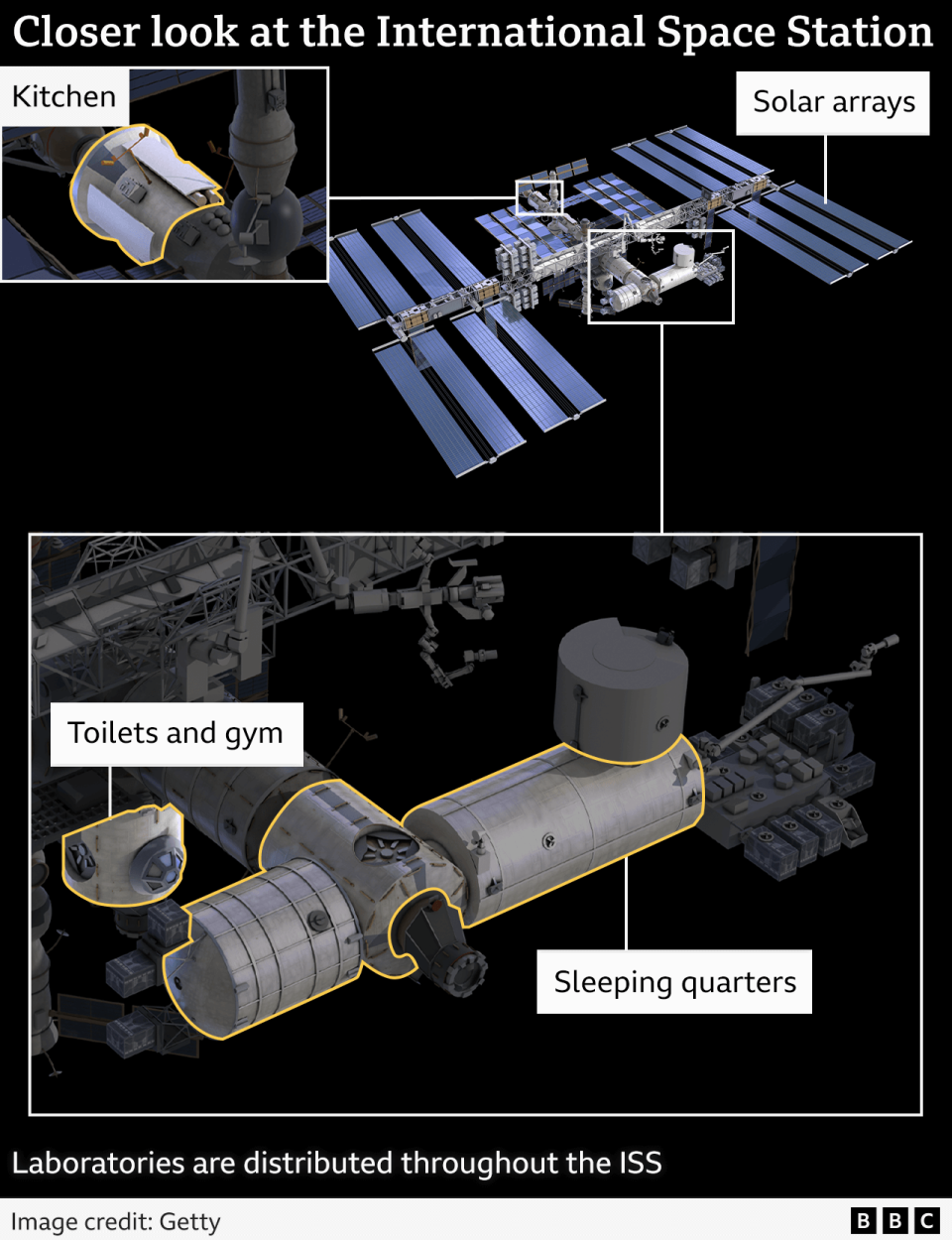

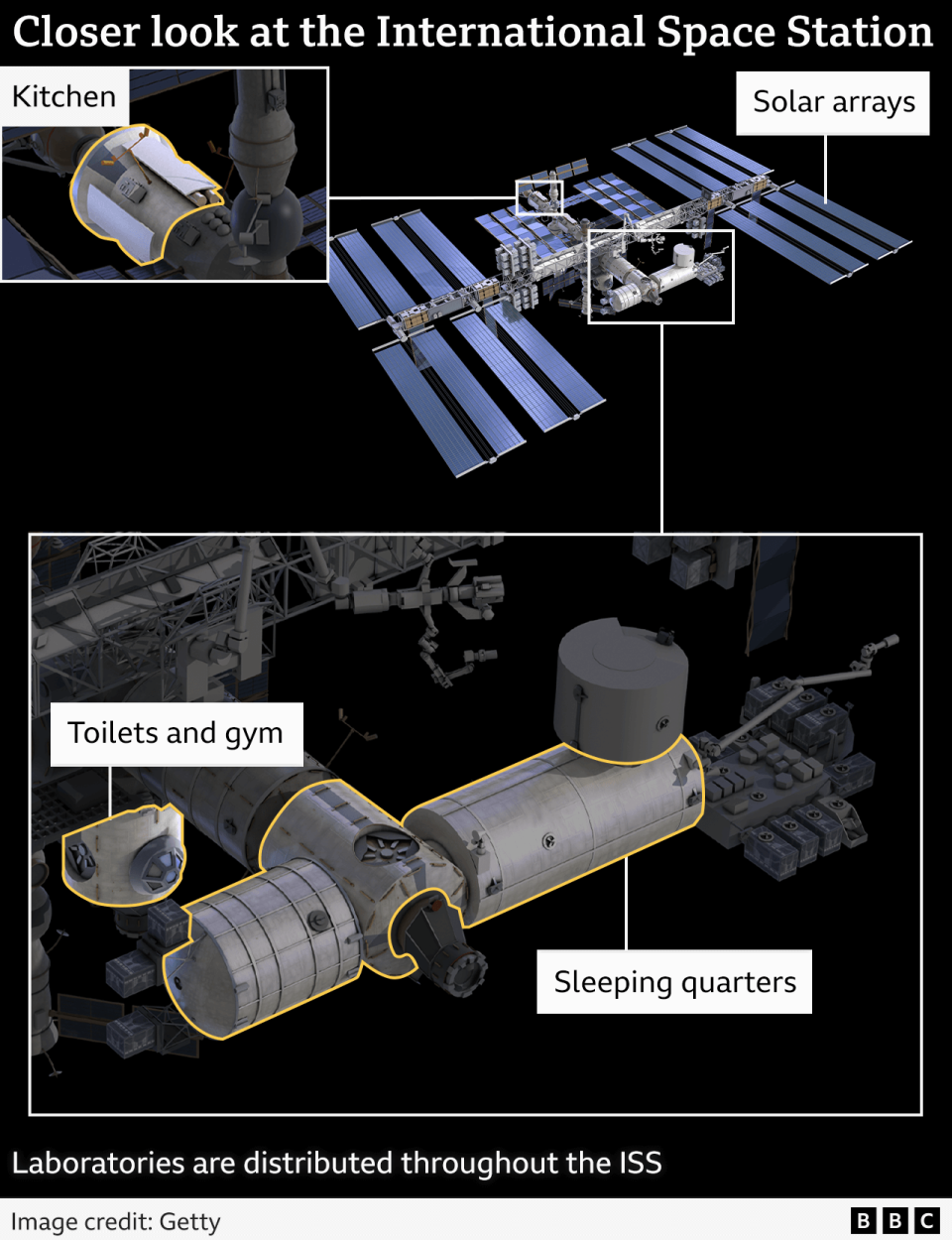

They wake early. At around 06:30 GMT, astronauts arise from the phone-booth dimension resting quarter in the ISS component called Harmony.

“It has the best sleeping bag in the world,” claims Nicole Stott, an American astronaut with Nasa that invested 104 days precede on 2 objectives in 2009 and 2011.

The areas have laptop computers so team can remain in call with household and a space for individual valuables like photos or publications.

The astronauts could after that make use of the restroom, a little area with a suction system. Normally sweat and pee is reused right into alcohol consumption water however a mistake on the ISS indicates the team needs to presently save pee rather.

Then the astronauts reach function. Maintenance or clinical experiments use up most time on the ISS, which has to do with the dimension of Buckingham Palace – or an American football area.

“Inside it’s like many buses all bolted together. In half a day you might never see another person,” describes Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, leader on the Expedition 35 goal in 2012-13.

“People just don’t go zipping through the station. It’s big and it’s peaceful,” he claims.

The ISS has 6 committed laboratories for experiments, and astronauts use heart, mind or blood displays to gauge their feedbacks to the difficult physical setting.

“We’re guinea pigs,” claims Ms Stott, including that “space puts your bones and muscles into an accelerated ageing process, and scientists can learn from that”.

If the astronauts can, they function faster than goal control anticipates.

Mr Hadfield describes: “Your game is to find five free minutes. I would float to the window to watch something go by. Or write music, take photographs or write something for my children.”

A fortunate couple of are asked to do a spacewalk, leaving the ISS for the area vacuum cleaner exterior. Mr Hadfield has actually done 2. “Those 15 hours outside, with absolutely nothing in between me and deep space however my plastic visor, was as stimulating and otherworldly as any kind of various other 15 hours of my life.”

But that spacewalk can introduce something novel to the space station – the metallic “space smell”.

“On Earth we have lots of different smells, like washing machine laundry or fresh air. But in space there’s just one smell, and we get used to it quickly,” explains Helen Sharman, the first British astronaut, who spent eight days on the Soviet space station Mir in 1991.

Objects that go outside, like a suit or scientific kit, are affected by the strong radiation of space. “Radiation forms free radicals on the surface, and they react with oxygen inside the space station, creating a metallic smell,” she says.

When she returned to Earth, she valued sensory experiences much more. “There’s no weather in space – no rain on your face and or wind in your hair. I appreciate those so much more to this day now,” she says, 23 years later.

< figcaption course=” caption-collapse”>[BBC]

In between working, astronauts on long stays must do two hours of exercise daily. Three different machines help to counter the effect of living in zero gravity, which reduces bone density.

The Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED) is good for squats, deadlifts, and rows that work all the muscle groups, says Ms Stott.

Crew use two treadmills that they must strap into to stop themselves floating away, and a cycle ergometer for endurance training.

‘One pair of trousers for three months’

All that work creates a lot of sweat, Ms Stott says, leading to a very important issue – washing.

“We don’t have laundry – just water that forms into blobs and some soapy stuff,” she describes.

Without gravity drawing sweat off the body, the astronauts obtain covered in a covering of sweat – “way more than on Earth”, she claims.

“I would feel the sweat growing on my scalp – I had to swab down my head. You wouldn’t want to shake it because it just would fly everywhere.”

Those clothing end up being so filthy that they are thrown away in a freight automobile that sheds up in the environment.

But their everyday clothing remain tidy, she claims.

“In zero-gravity, clothing drift on the body so oils and every little thing else do not influence them. I had one set of pants for 3 months,” she describes.

Instead food was the most significant danger. “Somebody would open up a can, for example, meats and gravy,” she claims.

“Everybody was on alert because little balls of grease drifted out. People floated backwards, like in the Matrix film, to dodge the balls of meat juice.”

At some factor one more craft could show up, bringing a brand-new team or materials of food, clothing, and devices. Nasa sends out a couple of supply cars a year. Arriving at the spaceport station from Earth is “amazing”, claims Mr Hadfield.

“It’s a life-changing moment when you catch sight of the ISS there in the eternity of the universe – seeing this little bubble of life, a microcosm of human creativity in the blackness,” he claims.

After a tough day’s job, it is time for supper. Food is primarily reconstituted in packages, divided right into various areas by country.

“It was like camping food or military rations. Good but it could be healthier,” Ms Stott claims.

“My favourite was Japanese curries, or Russian cereal and soups,” she claims.

Families send their enjoyed ones reward food loads. “My husband and son picked little treats, like chocolate-covered ginger,” she claims.

The team share their food the majority of the moment.

Astronauts are pre-selected for individual characteristics – forgiving, easygoing, tranquil – and educated to function as a group. That lowers the probability of problem, describes Ms Sharman.

“It’s not just about putting up with somebody’s bad behaviour, but calling it out. And we always give each other metaphorical pats-on-the back to support each other,” she claims.

Location, area, area

And ultimately, bed once again, and time to remainder after a day in a loud setting (followers run continuously to spread pockets of co2 so the astronauts can take a breath, making it regarding as loud as a really loud workplace).

“We can have eight hours of sleep – but most people get stuck in the window looking at Earth,” Ms Stott claims.

All 3 astronauts spoke about the mental influence of seeing their home world from 400km in orbit.

” I really felt extremely trivial because grandeur of area,” Ms Sharman says. “Seeing Earth so plainly, the swirls of clouds and the seas, made me think of the geopolitical limits that we create and exactly how really we are totally adjoined.”

Ms Stott says she loved living with six people from different countries “doing this work on behalf of all life on Earth, working together, figuring out how to deal with problems”.

“Why can’t that be happening down on our planetary spaceship?” she asks.

Eventually all astronauts must leave the ISS – but these three say they would return in a heartbeat.

They don’t understand why people think the Nasa astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore are “stranded”.

“We dreamed, worked and trained our entire lives hoping for an extended stay in space,” claimsMr Hadfield “The greatest gift you can give a professional astronaut is to let them stay longer.”

And Ms Stott claims that as she left the ISS she assumed: “You’re gon na need to draw my clawing hands off the hatch. I do not recognize if I’m going to obtain to find back.”

Graphics by Katherine Gaynor and Camilla Costa